After the manner of the Angelic Doctor, St Thomas Aquinas, we now inquire into the seasons of the year, whether they exist.

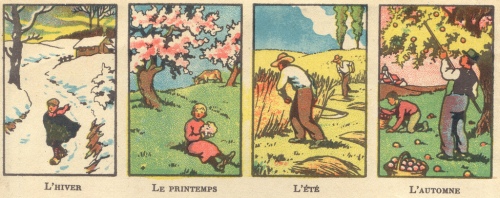

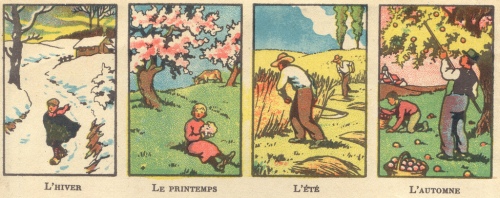

Objection 1: It seems that the seasons exist. Spring follows upon winter, winter follows autumn, autumn follows summer, and summer follows spring, in annual fourfold succession, as all attest.

Objection 2: Further, the seasons are observable in the changes they work upon plants in their sprouting, flowering and fruiting, and in the alterations of weather proper to each: cold and snow for winter, decreasing chill and intermittent rain for spring, heat and cloudlessness for summer, decreasing heat and intermittent storms and fogs for autumn.

Objection 3: Further, as it is written (and as Pete Seeger and the The Byrds have memorably repeated), “to every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven” (Eccles. 3:3).

On the contrary, the seasons cannot be said to exist, but they belong to the imagination. They may be said to subsist by human custom, but not in the regularity of manner commonly ascribed to them.

I answer that the arbitrariness of seasons is proved by the fact that the “season” assigned to 45 degree north latitude on the Ides of October (autumn) is not the same as the “season” assigned to 45 degrees south latitude on the same date (spring). Furthermore, the meteorological characteristics commonly ascribed to the seasons (e.g. heat, cold, rain, snow, fog, etc.) express themselves with notorious irregularly. The present winter on the western coast of North America, for example, has proved markedly unseasonal with a superfluity of warm, rain-free days. Seriously, it was like 80 degrees the other day. What the hell is up with that? A more suitable manner of calculating seasons might allow for the irregular assignment of spring, summer, autumn, and winter days throughout the year based on actual weather conditions. By such a scheme, any day of 70 degrees Fahrenheit or hotter – whether it occurs in February or in August – may be called a “summer day.” Likewise, any day of 35 degrees Fahrenheit or colder, or any day whatever with snowfall, may be called a “winter day,” even if it occurs in June. As prevailing conditions dictate, it may be that more summer days than winter days occur in the month of February, and more winter than summer days in the month of August. Likewise, the balance of the seasons need not be equally proportional but may favor summer one year, spring or autumn or winter the next.

Reply to Objection 1: Popular attestation, even if it be universal, does not establish the existence of any object or phenomenon.

Reply to Objection 2: At the equator there is no observable difference of vegetation or of weather to accord with the seasons as they are commonly differentiated one from another in more temperate regions.

Reply to Objection 3: The prophet Daniel affirms the arbitrariness of the seasons and their mere subsistence in custom when he says of God that “He changeth the times and the seasons” (Daniel 2:21). Further, human pretensions to meteorological knowledge are made null by our Savior himself when he says (Acts 1:7) that “it is not for you to know the times or the seasons.”